Note: Sidney John Kelly, Sr., was my great-grandfather. My mother is the daughter of Sidney Kelly, Sr.’s youngest son, Bernard L. Kelly. What follows was brought together from source documents I have acquired from the National Archives, the Naval History and Heritage Command, and the library system of the National Defense University, specifically the Joint Forces Staff College in Norfolk, Virginia. Copies of the Navy service records of Ensign Sidney J. Kelly, Sr., and QM3 Sidney J. Kelly, Jr. were obtained from the military records section of the National Archives. An abstract of the Army Service Record of Private Thomas Kelly was downloaded from the New York State Archives.

Tug E.S. Atwood

In 1916, Sidney John Kelly, Sr., was employed by Fred B. Dalzell & Company of 70 South Street, New York. They were agents for Sea, Harbor & Coast Towing. A letter from Fred B. Dalzell, dated March 29, 1917, stated that Sidney J. Kelly “has been employed by us as Master of our various tugs engaged in the transporting, docking, and undocking of vessels at various times covering twenty years.” Until December 1916, he was the Master of the tug E. S. Atwood. The letter, documenting Sidney’s profession, was given to the Third Naval District, headquartered in New York City, at the end of March 1917, less than a month before the United States officially entered the Great War.

Sidney Kelly was 42 years old in March 1917. He lived at 87 Adelphi Street in Brooklyn with his wife Emily and their children. Parents of seven, two sons would also go into military service before the armistice was signed in 1918. The eldest, Thomas Kelly (b. October 23, 1895), enlisted in the New York National Guard. Sidney J. Kelly, Jr. (b. October 24, 1897) would follow his father into the Navy. His youngest son, Bernard (b. March 16, 1903), had just turned 14. Sidney and Emily also had four daughters, Julia Alice (b. January 31, 1900), Irene Francis (b. February 14, 1906), Emily Augusta (b. January 12, 1908), and Edna (b. December 29, 1909).

Having made his career on the waters that make up the New York-New Jersey Estuary, Sidney possessed valuable knowledge and experience to the Navy. Like many professionals who made their livelihoods on the water, he was a member of the Naval Reserve Force, Class Four (Naval Coast Defense Reserve). The Naval Coast Defense Reserve (NCDR) was composed of members of the Naval Reserve Force capable of performing valuable services for the Navy or in connection with the Navy, defending the homeland from an attack from the sea.

Sidney Kelly first served in the NCDR during the Spanish-American War, providing harbor pilot service. He remained in the NCDR until March 1917, when he was activated as a result of President Wilson’s call-up of the Reserve Force as the United States declared war on Germany and her allies.

Sidney applied for enrollment as Boatswain with the Third Navy District. His application was initially denied. His physical attributes were presented in the “Descriptive List” on the report of rejection. He was five feet, four and a half inches tall, and weighed 116 pounds. He had blue eyes, dark brown and gray hair, and a complexion described as “ruddy.” The reason for his rejection read, “Depressed arches, 12 lbs, under weight (sic).” Because of the need for experienced Masters with knowledge of the currents in New York Harbor, a waiver was granted by Rear Admiral Nathaniel R. Usher, Commander Third Naval District, to enroll “Boatswain” Kelly. His service period was to run for four years, beginning on March 30, 1917.

Because quarters were not available on the Third Naval District’s Receiving Ship, the USS Glenville, Boatswain Kelly requested commutation of quarters. That request was approved, and he could live in the family home on Adelphi Street in Brooklyn.

USS Glenville (SP-2513) Photo from the Navy History and Heritage Command

Between April 1917 and April 1918, Boatswain Kelly’s duties involved piloting the USS Glenville, a modified ferry, and other steamships in and around New York Harbor. The Glenville ferried men and supplies from Manhattan and Brooklyn to Ellis Island, which the Navy was using as a way station to support fleet units coming into the harbor for provisioning.

On April 2, 1918, Boatswain Kelly was ordered to the Headquarters of the Third Naval District for shore duty. In a letter signed on the same day, he requested to be advanced to the rank of Ensign, United States Naval Reserve Force. His reasoning was based on his license as a civilian mariner and the duties he had performed for the previous year as “Acting Master of Steam Vessels” attached to the Navy Yard. He also noted his experience with minesweeping missions in the estuary.

His request was granted, and he was advanced to Ensign on April 4, 1918. On April 5, he returned to duty aboard USS Glenville.

Ensign Sidney J. Kelly and Emily Weaver Kelly, circa 1918. (Norman McDonald Collection)

Ensign Kelly’s two eldest sons served in the Army and Navy. Thomas M. Kelly enlisted in the National Guard in September 1917. He was initially assigned to the 23rd Infantry, New York National Guard. While training at Camp Wadsworth, South Carolina, the Army reorganized the New York National Guard troops into the 27th Infantry Division. Private Kelly was a member of Company G, 106th Infantry Regiment, 53rd Infantry Brigade, 27th Infantry Division, 2nd Corps of the United States Army.

Upon completing training in South Carolina, the 27th Division deployed to France as part of the American Expeditionary Force under General Pershing. In early May 1918, Private Kelly and the 106th Regiment boarded the troop transport, USS Abraham Lincoln, in Hoboken, New Jersey, for their transatlantic journey through U-Boat-infested waters. After a safe voyage, they disembarked at Brest, France, on May 23. From Brest, the Division moved to the vicinity of the town of Noyelles, where they spent their first of many nights under German aerial bombardment. The USS Abraham Lincoln was sunk by a U-Boat on the return trip from Brest to Hoboken within a week of dropping PVT Kelly and his compatriots in Europe.

The 2nd American Corps was placed under the command of the British Second Army and trained alongside their British Allies. On July 2, 1918, the 27th Division proceeded to Belgium near Ypres. The 106th Regiment was heavily engaged during the Ypres-Lys Offensive from August 21 to September 2, 1918. The Regiment was again directly engaged with German forces from September 24 to October 20 in the Somme Offensive, north of San Quentin, operating with the British Fourth Army against the Hindenburg Line. The Americans successfully breached the line, forcing a German retreat. The Americans paid a heavy price in casualties during the campaign.

With the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918. Plans for the return of the 27th Infantry Division began to take shape. Advance elements of the Division departed France for the United States in February 1919. Private Kelly and the 106th Infantry Regiment boarded USS Leviathan in Brest, France, in early May 1919 for the voyage home via the military terminals in Hoboken. They were among the last troops in the Division to make the transatlantic crossing. He was honorably discharged on June 10, 1919, upon demobilization of the New York National Guard. Private Kelly’s service record was lost, probably in a fire at the National Archives in the 1970s. However, the abstract of his service maintained by the State of New York indicates that he was not wounded or injured in action. The official history of the 27th Infantry, 106th Infantry Regiment, makes no mention of exposure to poisonous gas in any engagements either in France or in Belgium. There are family histories that indicate he was wounded in action and exposed to Mustard Gas. Without his actual service record and medical record, I cannot state with certainty if he was wounded. Given the severity of the fighting along the Hindenberg Line on the Western Front, it would be hard to believe he went through that kind of combat without injury.

Sidney Kelly, Junior, the second son of Sidney and Emily Kelly, enlisted in the Navy on June 6, 1918. He had been employed as a tug master and pilot for the Fred B. Dalzell & Company, the same company his father had worked before the war. The younger Sidney reported for initial training at Pelham Bay Naval Training Center in the Bronx, New York City.

Because of his work experience, the Navy designated him as a Quartermaster, Third Class. Quartermasters were responsible for the navigation of warships. He completed seamanship and quartermaster training before transferring to Naval Operating Base, Hampton Roads, Virginia (Norfolk), in October 1918 for Signal School. With the war winding down in Europe and a shortage of experienced tug masters in New York, the Navy granted his request to transfer to the inactive reserve in January 1919 and allowed him to return home to Brooklyn. He remained on the inactive rolls until September 1921.

In September 1918, Ensign Sidney Kelly, Sr., was issued orders as a Deck Officer aboard USS FOAM, a trawler leased by the Navy to conduct mine hunting and sweeping duties in and around the New York-New Jersey Estuary. USS Foam was homeported in Thompsonville on Staten Island. Foam operated in the Atlantic along the southwestern coast of Long Island down to the area of Colts Neck, as well as in the Narrows between Brooklyn and Staten Island, and New York Harbor.

Photo from the Navy History and Heritage Command Archives

Ensign Kelly Aboard USS Foam, 1918. (Norman McDonald Collection)

In the fall of 1918, the Spanish Flu became a worldwide pandemic. By the time it had run its course, over 50 million people would die of the disease. According to the Navy’s Board of Medical Survey Report on Ensign Kelly, he had come down with a case of the flu in November and was severely weakened. The report noted, “Patient states his mother had bronchial troubles, and that he has had a bronchial cough all of his life.” In January 1919, his cough became more severe, and he was transferred to the Naval Hospital in Brooklyn with acute bronchitis. Further tests came back positive for Pulmonary Tuberculosis. On February 14, he was released from the hospital to his home in Brooklyn.

The Navy Medical Survey Board recommended declaring Ensign Kelly medically unfit for service and separating him from the Naval Service. The recommendation went through the Navy bureaucracy until it was finally sent to the Bureau of Navigation at the end of February 1919. The Bureau of Navigation went about of medically discharging Ensign Kelly with final notification sent by letter on March 4, 1919, to the Third Naval District in New York. When the proper endorsements were made and the appropriate notifications prepared, the letter to Ensign Kelly arrived on March 13. The letter came hours after Sidney John Kelly had died at 2:40 AM on March 13, 1919. The official cause of death on his death certificate was listed as “Pulmonary Tuberculosis.”

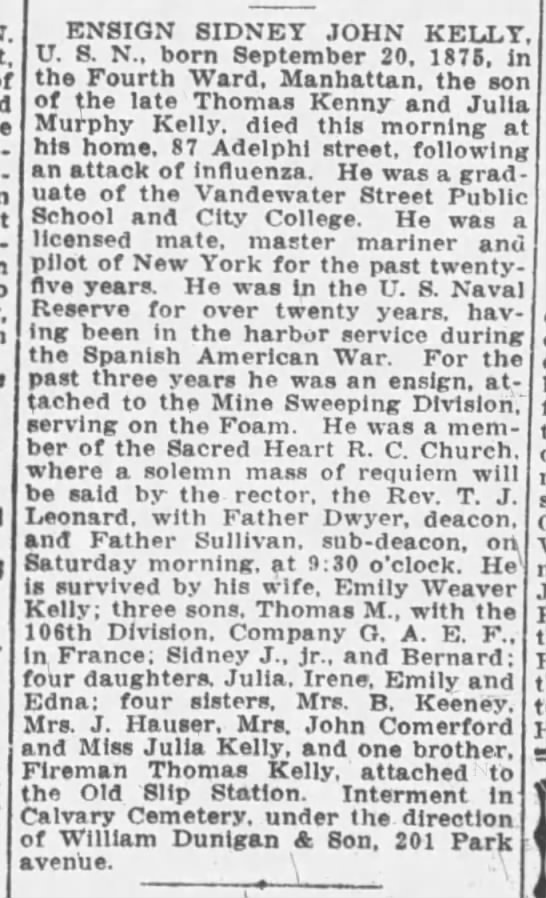

His obituary was published in several of Brooklyn’s daily papers:

Times Union, Brooklyn, New York, March 13 1919, Page 7.

He was buried in Calvary Cemetery in Woodside, Queens.

Ensign Kelly’s widow, Emily, would spend the next few months writing letters to the Navy to get his insurance and a widow’s pension. Because the medical discharge did not reach Ensign Kelly before his death, the Navy reversed the discharge paperwork to classify Ensign Kelly as having died on active duty. This reversal allowed Emily Kelly to collect her husband’s military insurance and qualify for a pension of $52 a month. It would take years of letter writing by Emily to completely correct his record, clear the references to the medical discharge, and obtain a clear statement of her husband’s service during the war.

Private Thomas Kelly returned from the war in Europe in 1919. He took a job at the U.S. Customs House near Battery Park in Manhattan. Never married, he resided with his mother until his death from cancer in 1952.

QM3 Sidney Kelly. Jr. returned to working on the water as a marine pilot in New York City. He married Else Höhn Hintermann; the couple had one son, also named Sidney. Sidney John Kelly, Jr., died of a heart attack in 1965

Emily and Sidney’s youngest son, Bernard, was too young to serve in the Great War. He would go on to a career in the Fire Department for the City of New York. In December 1942, as a Lieutenant, he was assigned to Engine 85, the marine unit operating fire boats in the waterways surrounding New York City. He married my grandmother, Regina O’Connell, and had four children: Bernard, Regina (my mother), Anne, and Maureen. Bernard L. Kelly died of cancer in 1960.

LT Bernard Kelly, FDNY aboard the Fireboat James Duane, circa mid-1940s

Amazing work!

On Sat, May 23, 2020 at 11:16 PM Michael’s Monologue wrote:

> Michael posted: “Note: Sidney John Kelly, Sr. was my great grandfather. > My mother is the daughter of Sidney Kelly, Sr.’s youngest son, Bernard L. > Kelly. What follows was brought together source documents I have acquired > from the National Archives, The Naval History and ” >

LikeLike

I am interested in learning more about MM2 Sydney G Kelly, Jr raised in the Pittsburg area. He enlisted in the Navy on July 20, 1943 and served with the SeaBees in the Asiatic Pacific. He was discharged in 1945.

LikeLike

You can start your search with the National Archives. In some cases, you need to state your relationship to the person you are researching. Email me here if you have specific questions.

LikeLike

Pingback: Letters From Home: World War I | Michael's Monologue